Seek and ye shall…

A database without a search function is like a car without an engine. The second part of our Base series is dedicated to implementing a database search.

Dmitry Naumov, 123RF

A database without a search function is like a car without an engine. The second part of our Base series is dedicated to implementing a database search.

The first part of this tutorial [1] explained how to create an image database with easy input masks and a tagging system (Figure 1). It satisfied the Base [2] claim that you can do database programming using mouse clicks instead of having to resort to SQL in Linux. Wizards and a graphical query editor do the work and let even users without programming experience create a database, forms, and queries.

Figure 1: Created from three tables, a query, and input form, the image database from the previous article was lacking only a search function.

Figure 1: Created from three tables, a query, and input form, the image database from the previous article was lacking only a search function.

The Base application from the first article lacked just one important feature: a search function (Figure 2). However, this task is one where the graphical helpers in Base are not going to help much – you can't do it without getting down and dirty with SQL.

Figure 2: No one wants to leaf through data records to find a particular image. The title search at the top of the form is what helps.

Figure 2: No one wants to leaf through data records to find a particular image. The title search at the top of the form is what helps.

A query that filters matching records by keyword is not something the graphical editor can handle. It requires SQL code – such as programmers use to communicate with the database – fortunately, you're only going to need homeopathic-like dosages.

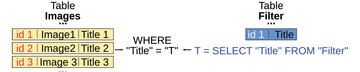

The task of inserting a user search string in an otherwise fixed query can be implemented in Base only through a back door. Figure 3 shows how it works. The Filter table (in yellow) contains only a record with a search string – in this example, the Title .

Figure 3: A subquery (in blue text) provides the main query (in black text) of the Title value as the single record of the Filter table. A subform that accesses Filter changes its value, thereby launching a search for the matching title.

Figure 3: A subquery (in blue text) provides the main query (in black text) of the Title value as the single record of the Filter table. A subform that accesses Filter changes its value, thereby launching a search for the matching title.

A subform changes the Title stored in Filter – similar to the Categories subform shown in the first part of this tutorial. The search query (in red) compares the Filter title with the Title fields in the Images table (in blue) and returns a record where the two match.

Figure 2 shows an extended version of the Images form. At the top, you can see the filter function highlighted in blue that searches for images with a particular Title . Leaving the field empty means scrolling through all the records as usual. Entering a value returns only those records matching the search string.

To build on the familiar, you can first create a table called Filter , which contains a VARCHAR field called Title that takes the modifiable search string. Allow Base to create a primary key for it automatically; otherwise, the content can't be changed by the form.

Next, you'll need another form that accesses the Filter table. Open the form navigator and right-click Forms to choose the Filter form. Because this form controls the data display in the previous main form, drag the MainForm to Filter to subordinate it.

The next step is to bind the Filter form with the table of the same name. Use the Forms button in the left button bar (the fourth from the top) to open the settings palette for the form.

Figure 4 shows the required settings for the Data tab. After selecting the table, you'll find the Cycle setting for Active record . This ensures that you don't add any new records but only change existing ones – because only valid entries can be used as search strings.

Significantly more complicated is the query that returns all records in Images that match the search string in Filter . That's where you need to write some SQL code. In the Base main window under Queries , select the Create Query in SQL View option.

The Base handbook [2], under the heading General remarks on database tasks and Data filtering , mentions having the SQL code you need to start with. Listing 1 shows an example based on our field and table name structure.

Listing 1

Search Query

SELECT * FROM "Images" WHERE "Title" = IFNULL( ( SELECT "Title" FROM "Filter" ), "Title" )

The entry SELECT * FROM selects all fields in the Images table, and the WHERE clause filters for specific record in which "Title" has to match the results from a second SELECT . This clause references the Filter table and specifies the value to match. The query thus extracts only those Title field values in Images that have the same value for the field in Filter . The IFNULL function, however, makes an exception if the Title field in Filter has a null value.

IFNULL returns the value from the first parameter, as long as it's not null; otherwise, it returns the Title value in the second parameter. The quoted string is evaluated as a field name from the first SELECT , so that it compares Title with itself, which is always "true" as long as the same field in Filter has a null value. The result is the filter function returns all records when a null filter value exists – at least in theory.

Unfortunately, SQL idiosyncrasies regarding the IFNULL function thwart the seemingly obvious assumption that a self-comparison always returns true . If the field is empty, for example, SELECT returns a NULL value, but the IFNULL gets an empty value, which is not the same as <NULL> as far as the database is concerned. Thus, an empty filter field can be missing all records where the Description field was not filled in.

If the workaround doesn't work for excluding the Title field in Images while designing the table with Input required = yes , the only solution is to encapsulate the return value for SELECT also with the IFNULL function (Listing 2).

Listing 2

Workaround

SELECT "Images".* , IFNULL( "Title", '' ) AS "T" FROM "Images" WHERE "T" = IFNULL( ( SELECT "Title" FROM "Filter" ), "T" )

Unlike the handbook, the example uses "Images" before the asterisk (* ) that is the wildcard for all fields in Images , even though it's clearly already indicated by the FROM "Images" clause. Without this workaround, Base 4.2.3 returns a syntax error, presumably from a bug in the SQL parser, because the redundancy makes little sense. Other Base versions don't have this problem, not even earlier ones.

The WHERE clause uses AS to compare the result of the IFNULL function with the result of the alias T value assigned to a new IFNULL function. The result is never NULL , but rather the empty value '' , which makes the filter query succeed.

Thus, MainForm no longer extracts its data directly from the Images table, but through the intermediate filter query. Therefore, you can change the data binding from MainForm to Filter: Query .

To have the filter function work from the form, you will need to do one more little thing. Give the MainForm a button (using the Push Button option in the Form Controls toolbar) and then choose the action Update form in the properties on the General tab. Only after the first click on this button will MainForm show the matching record in the filter field.

The search function can be extended to other data fields. Each additional field calls another IFNULL function in the SELECT clause at the beginning of the query, as well as an IFNULL function in the SELECT clause that encapsulates the subquery. Listing 3 shows how this is knit together.

Listing 3

Putting Things Together

SELECT "Images".* , IFNULL( "Title", '' ) AS "T" , IFNULL( "Author", '' ) AS "A" FROM "Images" WHERE "T" = IFNULL( ( SELECT "Title" FROM "Filter" ), "T" ) AND "A" = IFNULL( ( SELECT "Author" FROM "Filter" ), "A" )

Note, however, that the Filter table needs an additional column for each search field with the same data type as its counterpart in Images (e.g., Author of type VARCHAR ). The subform for the search also needs an additional text field where you can modify the author names in Filter .

It's frustrating how quickly the principle of "click together" reaches its limits in Base. Even comparing table fields with each other loses its effectiveness in the graphical query editor. Fortunately, this sample database required an order of magnitude less code than a similar web application in Perl or PHP.

However, Base leaves a significantly less mature impression than LibreOffice text processing. The frequent program failures also add to this, some of which even cause database corruption in the worst cases. Consider well if you want to entrust critical data to Base. You should probably use an external database engine such as MySQL or PostgreSQL instead.

If you want to expand on the example given here, you can find comprehensive and clear guidance from the official handbook [3]. The online help accompanying the program is rather useless in comparison. l

Infos